As you approach the rustic log and glass front of the Adirondack Store on Route 86, in Ray Brook, between Lake Placid and Saranac Lake, a glance through the window promises memorable browsing.

From the Archives

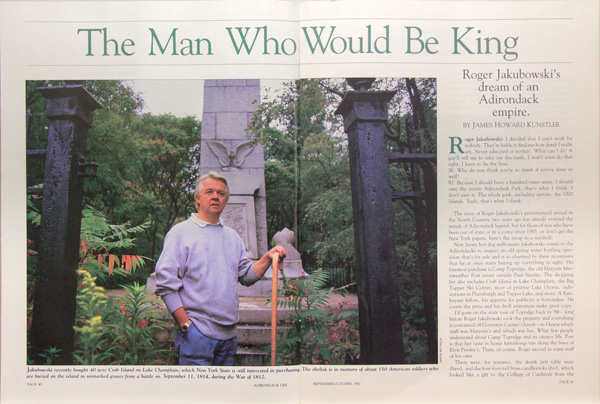

The Man Who Would Be King

The story of Roger Jakubowski’s preternatural arrival in the North Country two years ago has already entered the annals of Adirondack legend, but for those of you who have been out of state or in a coma since 1985, or don’t get the New York papers, here’s the recap in a nutshell:

New Jersey hot dog millionaire Jakubowski comes to the Adirondacks to inspect an old spring water bottling operation that’s for sale and is so charmed by these mountains that he at once starts buying up everything in sight. His foremost purchase is Camp Topridge, the old Marjorie Merriweather Post estate outside Paul Smiths. The shopping list also includes Crab Island in Lake Champlain, the Big Tupper Ski Center, most of pristine Lake Ozonia, radio stations in Plattsburgh and Tupper Lake, and more. A flamboyant fellow, his appetite for publicity is bottomless. He courts the press and his droll utterances make great copy.

An Au Sable Forks Pulitzer: The Life My Father Chose

Spike Pulitzer (1941–2013) was a paradox, even to those who knew him well. He was complex yet simple, tough but tender, guarded and private, yet genuine and transparent. When exchanging gifts at Christmas he would preface many of his own with, “Now, before you open this, there’s a little explanation.” It drove us nuts. In retrospect, this made sense. To really understand my dad a little explanation was needed.

The Derry Queen

Google “floating picnic table” and it’s easy to fall into a rabbit hole, chasing one link after another to curiouser and curiouser contraptions. I stumbled onto one of those contraptions a couple of years ago as I noodled around on Pinterest.

New Wave

In early December, John Davis, a wilderness advocate, was riding his bike on a dirt road near his home—a cabin deep in the woods—a few miles outside of the town of Westport. Davis has lived here for nearly three decades and knows the area’s hills and valleys better than just about anyone, so the presence of a “For Sale” sign on 70 acres of forestland caught his eye.

My Adirondack Life

When people ask me about my life as a black person growing up in the Adirondacks among a predominately white population during the 1950s and ’60s, several persistent images explode in my mind.

A Glass House of Our Own

Among the great camps, peaked roofs and proud lodges of the Adirondack Park, an early modernist work by one of America’s most influential architects remains overlooked and underappreciated by all but a few historians, neighbors and design buffs. The minimalist house has flat roofs, high ceilings, expansive open spaces and walls of windows. These are common characteristics among contemporary homes, but this one stands out for the area and era in which it was built. Philip Johnson, the renowned architect, designed the structure erected on Willsboro Point at the same time he completed his own world-famous residence, the Glass House, in New Canaan, Connecticut.

It was 1949. Johnson’s career as a practicing architect was barely underway. He was 42, had completed only three other homes, and was already hard at work on the Glass House when a well-heeled young couple commissioned the Willsboro residence. George Eustis Paine Jr. and his bride, Joan Widener Leidy, both in their 20s, belonged to prominent, art-loving families from New York and Newport society

Always on the Lookout

You are a college student from Albany, or a doctor from Montreal, or the mother of an athlete playing in a hockey tournament in Lake Placid, and with a friend or relative or two you have decided to climb a mountain in November. You’ve driven to Adirondak Loj, piled out of your vehicle into brisk morning air. Your boots have barely touched the snow and gravel of the parking lot; you’re hauling out your pack. You’re aware of an approach: you hear a “Good morning!” and you turn to answer a lean figure of medium height in a forest green wool jacket, olive pants, and climbing boots almost black with use and care. He has stopped at a polite 10 feet. Observant blue eyes scan your group from under a dark green cap or balaclava. “May I be inquisitive?” he asks. “Where are you planning to go today?”

“Marcy,” you say, or “Algonquin,” or “Colden.”

“May I ask if you’re carrying crampons.”

You don’t own such things. There’s bare ground all around. It’s warm for the season and the peaks looked newly dusted with white as you came along the Loj road.

“In that case I’d like to make a suggestion. Do something else.”

General Stories

The four corners in Stony Creek meet at the crossing of two roads to nowhere. One peters out among the hunting camps and logging roads past boggy Lens Lake; the other segues into a four-wheel drive roller coaster through the climax white pines on the way from Harrisburg to Wilcox Lake, fourteen long lonely miles west.

The corners are the hub of whatever commerce takes place here, which is precious little: two general stores facing two taverns in a pattern like a swastika. Little Roaring Branch bisects the quadrangle before debouching into Stony Creek proper 100 yards downstream, where a century ago tanneries supported a population of 1200, three times the present one. For the newcomer, arriving here can be like stepping into a Conan Doyle or Edgar Rice Burroughs fever dream: a Lost Valley where every living creature refutes Darwin and the laws of physics as we know them do not apply.

The Way It Is in Beaver River

First the waters rose, cutting off the one, tenuous road connection. Decades later; the railroad stopped running. And so Beaver River, once a bustling lumber camp in the western foothills of the Adirondacks, became an isolated island in a sea of trees, the only settlement in New York State today which is accessible by neither road nor trail.

For some communities, the loss of rail service is a major misfortune, and the lack of any road links to the outside world would mean certain death. And, indeed, at first glance Beaver River appears to have borne fortune’s blows poorly. In physical appearance the town is little more than a clearing in the woods, crisscrossed by narrow dirt roads and the rusting railroad tracks, dotted by the homes of its IO permanent residents and the “camps” of nearly a hundred seasonal residents.