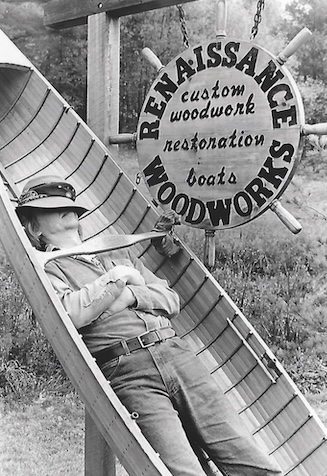

Martha and Fred photograph from the Adirondack Experience

Martha Rebentisch fell sick with the same disease that killed her mother. She dropped out of high school and left home in New York City to fight for her life at sanatoriums, where clean country air was the only hope for survival from tuberculosis, rampant at that time.

According to the Center for Disease Control, in the late 19th century and well into the 20th, one out of every seven people living in the U.S. and Europe succumbed to the bacterial disease. The odds were awful. In 1927 Martha came to Saranac Lake for treatment at the Trudeau Sanatorium, where she underwent a handful of procedures, including a thoracoplasty—removal of ribs from the chest wall to collapse the lung, the goal being to rest the organ and inactivate the disease.

She was still so sick, stuck in bed and, as the years fell away, losing hope.

The story, one that’s been repeated again and again in the Adirondack canon, is that Martha saw an advertisement in a local newspaper in which a local guide offered to take an “invalid” into the woods for the summer to convalesce. That guide was carpenter and boatbuilder Fred M. Rice, by then in his mid-50s and an expert and well-respected woodsman. It was 1931, the Great Depression in full swing. Fred and his wife, Kate, likely needed the money that would come from a long-term guiding gig. But living in Saranac Lake among so many TB patients taking the “fresh air cure”—sitting cocooned in blankets outside on porches—Fred wondered if there was a better way to wellness that involved the natural world, where you could hike and fish and paddle, muscles moving, lungs pushing mountain air in and out. He also figured that if anyone answered his ad it would be a man. He got Martha, ready to try anything to save her life.

What followed were six years of Fred and Martha camping in a platform-tent, spring through fall, on Weller Pond—an amoeba-shaped appendage of Middle Saranac—immersing themselves in the Adirondack wilds.

Martha got better. And she grew to prefer this solitary life surrounded by peaks, water and wildlife to anyplace else. She methodically journaled about her days at Weller, eventually compiling her entries into a best-selling memoir, The Healing Woods: How My Search for Health in the Woods Opened Up a New Way of Life, published in 1952 under the name Martha Reben. Two more books about her time in the outdoors with Fred followed—The Way of the Wilderness and A Sharing of Joy. She died in 1964 at 58, an age that exceeded anyone’s expectations.

Today Martha’s books are out of print, though you can find them in most Adirondack public libraries. Her writing relays how days were passed, with observations about flora, fauna, weather, seasons—a world we often overlook, trumped by the chaos of our modern lives.

Martha repeatedly credited Fred for saving her life and, yes, he brought her to the woods and showed her what to do. But it was the woods themselves, the ripple of Weller’s water, Boot Bay Mountain up above and the creatures she encountered that brought her back.