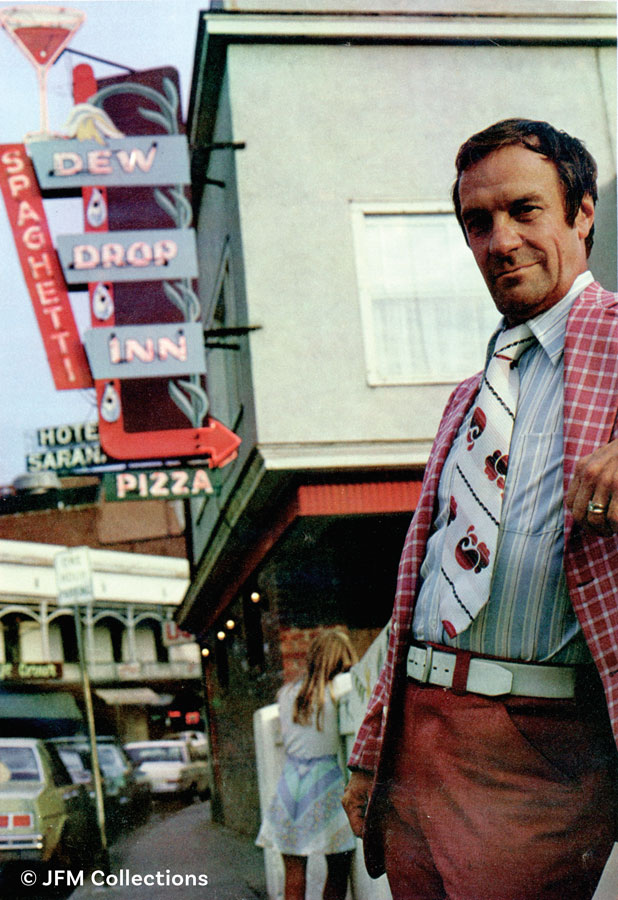

Photograph courtesy of the Plattsburgh Air Force Base Museum

On Christmas Day, 1964, Colonel Richard Stewart was on high alert as he almost always was.

Commander of the 820th Strategic Aerospace Division in Plattsburgh, Stewart’s arrival at the air base a year prior had come as North Country residents were wrapping their heads around broadcast television, a brand new interstate highway and, more to the point where Stewart was concerned, the installation of 12 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) that put Plattsburgh and environs on the leading edge of a burgeoning arms race with the Soviet Union.

Stewart’s objective that day was to spread some Christmas cheer among his men and to provide the managing editor of the Plattsburgh Press Republican with a personalized tour of a missile site’s inner workings—which today might seem out of character for a military steeped in classified this and top-secret that.

But after some initial denials, the North Country nukes became front page news, their fearsome firepower aimed at the Russian motherland, but also at the American psyche, which had been bruised by our perceived nuclear shortfall in comparison with the Soviets.

This “missile gap” had become political fodder in the late 1950s, even though high-altitude flights of Lockheed’s U-2 spy plane showed there to be no such thing. The Soviets were methodically building bombs, it was true, but they had limited launch capabilities and it was the Americans who had the numerical advantage by far.

Still, image is everything, and in the late ’50s, according to CIA documents declassified in 2011, President Eisenhower acknowledged that the “political and psychological impact” of a major nuclear buildout was of “critical importance,” and ordered the acceleration of weaponry, the destructive capabilities of which the world had never seen.

That buildup gave “highest priority” to four missile systems, including the capable yet dated Atlas rockets famous in pop culture for sending chimps into space. All of these new installations would be west of the Mississippi. Except one.

In 1959, a loose-lipped property owner in Au Sable Forks blabbed that the Air Force was drilling test holes on a ridge east of town, looking for a suitable location for an ICBM silo. Questioned by the press, the Air Force acknowledged they’d been out surveying the hinterlands, but said they did that kind of thing all the time, more or less for the fun of it. The Pentagon denied knowing anything about it at all.

But Au Sable Forks would indeed become one of a dozen rural installations forming a tight ring around the Plattsburgh base—eight missiles were in Clinton County, with two each in Essex County and northern Vermont. One spare was kept at the Plattsburgh base.

To do the job, thousands of workers, from local laborers to technicians from the nation’s most renowned defense industries, feverishly carved out 12 subterranean silos and accompanying underground command posts, each silo large enough to accommodate the Statue of Liberty. “Did it cause chaos? Oh, my gosh, yes,” said Jeff Stephens, a leading expert in North Country missiles.

The initial secrecy surrounding the North Country missile program had not lasted for long.

Newspapers wrote dozens of stories about the installation. Everybody knew the location of these silos, as well as granular details about launch procedures and rocket capabilities. Over and over the papers printed the timeline. Fifteen minutes to fuel and take aim. Twenty-six minutes to the target. The end of the world as everyone knew it in 41 minutes flat. Our outgoing missiles and the Soviet incoming missiles would pass each other on the way. The name for this hellish hailstorm of nukes was Mutually Assured Destruction, whose acronym said it all.

Any Soviet with a subscription to the Press Republican would have had a front-row seat to our growing nuclear capability. Which, of course, was the point. The Plattsburgh missiles were deadly serious business, but they were also an exercise in optics: Don’t mess with the U.S.

Between 1962 and ’65 a dozen Atlas missile installations ringed Plattsburgh’s Air Force Base. Map by Matt Paul

The community’s view of the ICBMs was complex.

Some felt it showed the government believed country folk were expendable. Farmers who sold the ground grumbled not about incoming rockets, but that the government lowballed the price. The Air Force assured residents that the sites would not themselves be targets, because they could only be destroyed by a direct hit, and the odds of 12 direct hits were so small that the Soviets wouldn’t bother to try. Besides, the Plattsburgh base itself was already a target, and with the Soviet missile’s lack of pinpoint accuracy, they were just as likely to hit Montpelier.

More concerning, perhaps, was the safety of our own missiles. When something went haywire with a liquid-fueled Atlas rocket anywhere in the nation—usually involving a massive fireball with negative effects on anyone who happened to be nearby—it was front-page news in North Country papers.

Yet all things considered, Stephens said, the locals considered it “a badge of honor” to play a key role in our national defense. To be important enough for the Reds to target right there with great industrial cities like Pittsburgh and Cleveland was a sort of nuclear-age validation of self-worth.

When the first Atlas arrived by cargo plane in 1962, it was greeted not with foreboding, but with excitement. Community leaders were invited to inspect the weapon, an event that was followed by a celebratory dinner. Business leaders toasted the missile program’s benefits to the economy and employment rate.

The cost was of course enormous, especially considering that almost from the day these missiles were trucked in, the Pentagon was making plans to truck them back out.

The missile age came to the North Country with the brightness and brevity of a muzzle flash, gone before anyone was quite sure what they had seen. Yet it burned an image onto regional retinas that remains to this day. The quintessential photo from the era was of a gleaming Atlas F rocket sitting atop a launch pad, with majestic Whiteface Mountain in the background, the incongruity of which would today make the average critical thinker assume it had to have been photoshopped.

Even before they arrived, newspaper editors were fretting they wouldn’t be here long. The Atlas was fueled by a boilermaker of kerosene and liquid oxygen that, unlike solid propellants, couldn’t be stored onboard. In terms of nuclear war, the 15-minute fueling time was an eternity. Newer rockets also had onboard navigation systems, while the Atlas had to be guided by land-based computers.

The newspapers were right; a month before Stewart’s Yuletide rounds, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had officially announced what everyone by then already knew. The Atlas had served its purpose.

This left the question of what to do with the vacated launch sites. Before the missiles had even arrived, editorials predicted “the (abandoned) silos will be virtually useless.” They were mostly right about that too, although it hasn’t stopped people from trying.

The sites remain to this day—they were not imploded as many were in accordance with nuclear arms–reduction treaties because, going forward, they were not seen as posing any particular international threat. The greater risk has been to the private hands into which they have fallen over the years, as anyone who has ever priced insurance on a seemingly bottomless pit filled with water and jagged metal can attest. (The construction sites killed more Americans than Russians; in the first year, four workers lost their lives to collapsing scaffolding and falling boulders, including the father of six children.)

Still, the romance of owning one’s very own nuclear missile installation has had its appeal, and plans, some realized, most not, to fashion them into something useful have abounded.

The most commercially successful has been the Lewis site, home to Unconventional Concepts Inc., a company that tests advanced military systems.

The underground cavity is dead silent and free from other ambient interference, a necessary asset for such a laboratory. A proposal for above-ground testing of howitzers in the Adirondack Park has been met with criticism from conservationists and stony silence from the Adirondack Park Agency, but the company is otherwise regarded as a good neighbor, said Lewis town supervisor Jim Monty, most notably for wiring the neighborhood with broadband—another throwback to the past, as it was the silos that brought superior electrical and phone lines to rural communities more than a half-century ago.

Other silo owners have conceived of subterranean homes, beer caves, discos, survivalist condominium housing (really) and, naturally, wedding venues. Some have succeeded, but for most the realities of a 170-foot hole in the land of the 20-foot water table added up to an ugly mosaic of water, rust and mud.

Today the silos seem most valuable for their memories. No matter how short-lived, Stephens said, they were a critical bridge at a time of great uncertainty. They held the dike until bigger and better systems could be developed.

They are also memorable for the missileers who served. “They went down for their shifts knowing that when they came back up their families could be dead and the world they had known would be gone,” Monty said.

But Armageddon never came. Perhaps in some small way, the North Country helped see to that.